I usually think of my time in Russian-speaking countries as a time to charge up my language batteries. Sure, I use Russian basically everyday, either for my research or because something interesting pops up on my Facebook feed. This tends to be a pretty narrow range of source material—academic articles and newspaper articles, basically. My conversational Russian tends to decline over the course of the academic year because I just don’t speak it very much. Being in a Russian-speaking country gives me the chance to practice speaking again and soak up as much Russian-language input as possible. Plus, it’s a lot more fun to work on learning a language if you have the chance to go out and put things into use every day.

I’d been wanting to do some reading over the summer, mostly short novels by postwar Soviet authors that I’m interested in. Unfortunately, after a long day of sitting at the archive and reading letters and bureaucratic documents in Russian, these books just weren’t getting me motivated.

Browsing in Respublika, a cool chain of bookstores here, I picked up a couple of novels by contemporary Russian writers—Pokhoronite menia za plintusom (Bury Me Behind the Baseboards) by Pavel Sanaev and Shpionskii roman (Spy Novel) by Boris Akunin. I’ve always wanted to get into contemporary Russian fiction, and these books looked promising. I started with Bury Me Behind the Baseboards. Written in the ‘90s, the book was a cult classic for years until it suddenly became a huge bestseller in the 2000s. It is the story of a sickly eight-year-old boy who is being raised by an overbearing grandmother who curses him out practically on an hourly basis. It’s basically a charming tale of borderline child abuse. Suffice it to say, I got to page 76 and threw in the towel. It just wasn’t working for me.

Browsing in Respublika, a cool chain of bookstores here, I picked up a couple of novels by contemporary Russian writers—Pokhoronite menia za plintusom (Bury Me Behind the Baseboards) by Pavel Sanaev and Shpionskii roman (Spy Novel) by Boris Akunin. I’ve always wanted to get into contemporary Russian fiction, and these books looked promising. I started with Bury Me Behind the Baseboards. Written in the ‘90s, the book was a cult classic for years until it suddenly became a huge bestseller in the 2000s. It is the story of a sickly eight-year-old boy who is being raised by an overbearing grandmother who curses him out practically on an hourly basis. It’s basically a charming tale of borderline child abuse. Suffice it to say, I got to page 76 and threw in the towel. It just wasn’t working for me.

It was at that point that I dipped my toe back in the waters of All Japanese All the Time for some inspiration. For the uninitiated, the website is written by Khazumoto, a guy who taught himself Japanese in a couple of years mostly through immersion and flashcards. His methods are unorthodox, his sense of humor is warped, but the site is addictive. I stumbled across his article “Why the Way We Read Sucks, and How to Fix It” and it seemed like it was written to solve my reader’s block.

In the article, Khazumoto’s basic point is that we should control our reading, and not let it control us. Тhe way we are taught to read in schools as beginner readers isn’t always the best strategy for reading for the rest of our lives.

"The style of reading that is typically taught and/or encouraged in school is all about:

- Hitting every single word.

- No change of pace or shifting gears.

- No skipping unless teacher says so. Any self-directed skipping is “cheating”, and is to be punctuated by feelings of guilt and remorse (aren’t these, like, synonyms?).

- Zero or severely limited choice in terms of start time, stop time and duration.

- Zero or severely limited in terms of reading material, with no option to change after initial choice.

- The order in which the book is written and presented is the One, True and Only Correct Order. You have no right to permute it or ignore it. You earn the right to read page p+1 only after perfectly reading page p.

It’s no wonder that so many adults never pick up another real book once they leave school. If you’d never ever been allowed to set or change the channel on your TV, and never been taught that you even had the right or ability to make such a judgment call, then you’d probably hate TV, too — no matter how many “TV-worms” (think: bookworm) told you that TV was the shizzle and that there were tons of great channels and shows out there."

I realized this was the problem I was having with reading in Russian. I was like a person watching TV who wasn’t letting themselves change the channel until long after they were bored. While the strategy of hammering your way through a book come hell or high water may work if you absolutely have to read that specific book, if your goal is just to get more Russian text into your brain, then you have to be prepared to abandon reading material as soon as you notice that it is dragging you down. If you’re not having fun reading something, you’re not going to want to do it, and you’ll eventually sabotage your own language-learning project. So, I resolved to give myself permission to ditch Bury Me Behind the Baseboards.

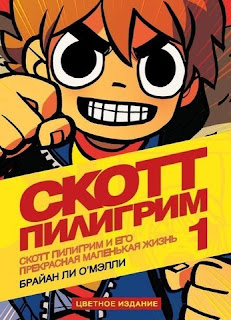

Luckily, this decision coincided with my discovery of the comics section at another great bookstore, Moskva. Comics, both locally-produced and imported, have just started catching on in Russia in the last few years. Previously, they were only available in bootleg translations (“scanlations”) on the internet (for example, this translation of Scott Pilgrim was a true labor of love). In another one of Khazumoto’s articles, “You Can't Afford Not to Buy Japanese Books,” he makes the point that buying books is an essential part of the language learning process. It’s not optional—it’s fuel for your fire. This conveniently helped me justify buying a bunch of different Russian comics (mostly translated, including Blue is the Warmest Color, Scott Pilgrim, and Adventure Time).

So now I’ve been working my way through a big stack of comics. My method—again borrowed from All Japanese All the Time—is to look up any words that look interesting, and then copy entire sentences into a flashcard program called Anki. I’m pretty picky with what sentences I decide to put in Anki because making the cards is time-consuming, but it really helps to learn vocabulary in context.

So now I’ve been working my way through a big stack of comics. My method—again borrowed from All Japanese All the Time—is to look up any words that look interesting, and then copy entire sentences into a flashcard program called Anki. I’m pretty picky with what sentences I decide to put in Anki because making the cards is time-consuming, but it really helps to learn vocabulary in context.

Finding the comics has actually become an adventure all its own. I was surprised to discover that Moscow has multiple comic book stores. I checked out two: Chuk i gik and Rocket Comics. Both are pretty bare bones compared to your usual packed-to-the-gills comic book store in the states, but the staff was really nice and ready to offer suggestions. Ultimately, I think the only way to keep improving your language skills is to find a hobby that you can do in your second language. When you have a hobby, language learning doesn’t feel like work. Moreover, it helps you find other people with similar interests, which in turn makes you feel more at home in a foreign country. (Example: after chatting with the comic book store guy at Rocket Comics and expressing an interest in local Russian comics, he gave me a whole stack of them for free!) Overall, I think an ounce of creativity in designing your own personal language-learning project goes a lot farther than a pound of discipline.

Well, Volume One of Scott Pilgrim (color edition!) is calling my name, so I think it’s time to wrap this up!

No comments:

Post a Comment